Mining with meaning: Indigenous voices in environmental scans

Topics

Featured

Share online

Learn more about the Master of Arts in Environment and Management.

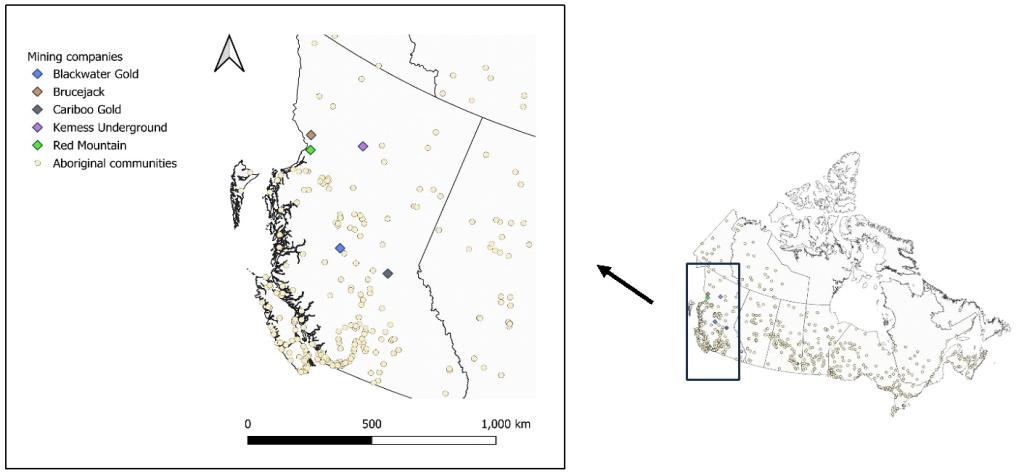

Proposed mining projects in Canada are required to undergo impact assessments to evaluate their potential environmental and social effects long before the first shovel pierces the ground. With more than half of those projects located on or near Indigenous territories, input from Indigenous communities is critical to creating a complete picture of potential harms.

Royal Roads University’s Cecilia Campero, an adjunct professor of Humanitarian Studies and associate faculty in the School of Business, is leading a research project to better understand how Indigenous Knowledge can influence environmental impact assessments to address the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals on their land and territories, and how environmental governance regimes account for actions and outcomes of integrating Indigenous Knowledge and the SDGs.

The project, titled Indigenous Knowledge and the Sustainable Development Goals: Understanding the Actions and Outcomes of Environmental Impact Assessments in BC, is funded by an Insight Development grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

“Impact assessments are tools used by decision makers for the approval of new development projects, programs or policies, to identify potential impacts and propose adaptation or mitigation strategies,” explains Campero, who is a scholar with Indigenous Mapuche heritage. “These are knowledge-based tools. So what knowledge are we accounting for? Whose knowledge is important in this decision making?”

She adds: “I want to highlight the importance of Indigenous Knowledge. But I also want to emphasize that knowledge is not just about data — it's also about acknowledging their sovereignty, their territories, their cultural practices.”

Indigenous Knowledge can include information collected and developed over generations about local ecosystems. For example, a key outcome of integrating Indigenous Knowledge in achieving the zero-hunger SDG is generating a holistic approach to food security — one that considers not only human needs, but also the well-being of wildlife.

“[Including] Indigenous Knowledge [in an impact assessment] allows you to have new methodologies, and understand seasonal patterns, environmental trends, all these components that ‘Western science’ may miss,” Campero says.

Adriana Lelio is a student in RRU’s Master of Arts in Environment and Management program and a research assistant on the project. Lelio says the questions that most often come up in impact assessment conversations with Indigenous communities are around local food systems, including harvesting, hunting and fishing, the access to safe drinkable water and other impacts.

“These worldviews are completely different and extremely valuable. They are so rich, they are so complex and deeply holistic,” says Lelio, an Argentinian who also has Mapuche heritage.

“Indigenous Knowledge integration and local consultation in impact assessments is a cultural recognition, social recognition and an act of humility towards meaningful reconciliation,” she says. “It paves the road towards social licence for resource developments such as mining projects… which implies the possibility to sustain that project in the long term, diminish conflicts and reduce environmental and social impacts.”

More than half of proposed mining projects in Canada are located on or near Indigenous territories. Therefore, input from Indigenous communities is critical to creating a complete picture of potential harms.

Campero and Lelio agree that thorough mining impact assessments shouldn’t just “tick boxes” for consultation with Indigenous communities – but ask for and listen to Indigenous input and incorporate that knowledge into the resulting plans which will protect and benefit the impacted communities.

Learn more about the Master of Arts in Environment and Management.